As you can imagine, part of doing a blog on Warner’s Safe Cure involves research. Although I would consider myself to be knowledgeable about H. H. Warner and his patent medicine empire, I am always reminded of how much remains to be discovered. Part of my research includes looking at the vast array of advertising that Warner used to develop his brand. That includes newspaper advertising, almanacs, trade cards, posters and on and on.

Warner’s Safe Rheumatic Cure Ad in the American Reformer on December 6, 1884

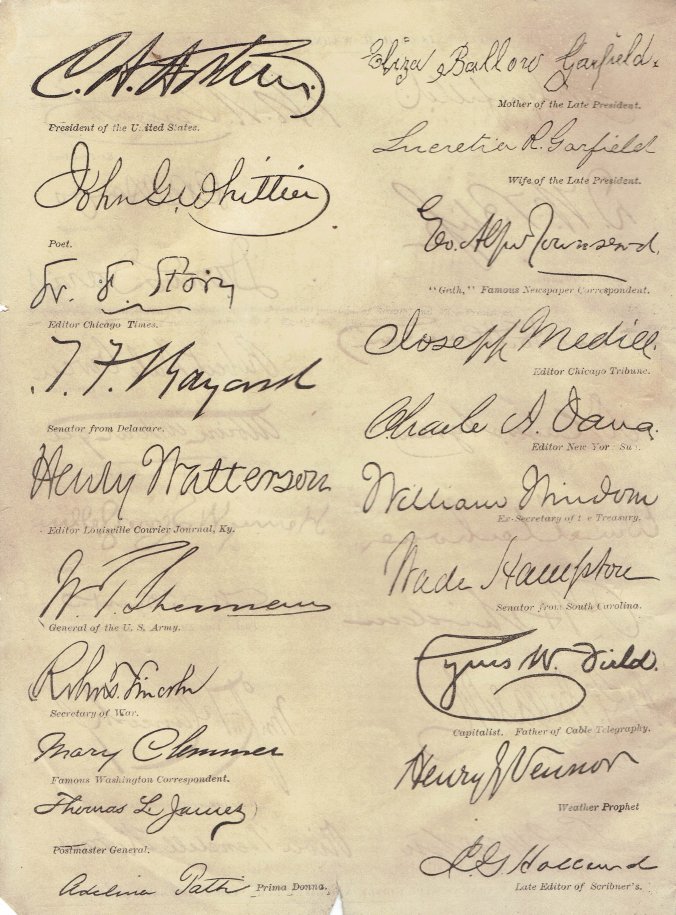

When you look at that much advertising, you start to notice that certain themes emerge repeatedly as well as certain images. Warner was a master at using the media available in the 1880’s to make his product a household name. For example, much of Warner’s advertising was designed to encourage potential customers to take charge of their own health with the help of Warner’s Safe Cure. Ironically, Warner also made frequent use of testimonials by physicians, who recommended the use of Safe Cure.

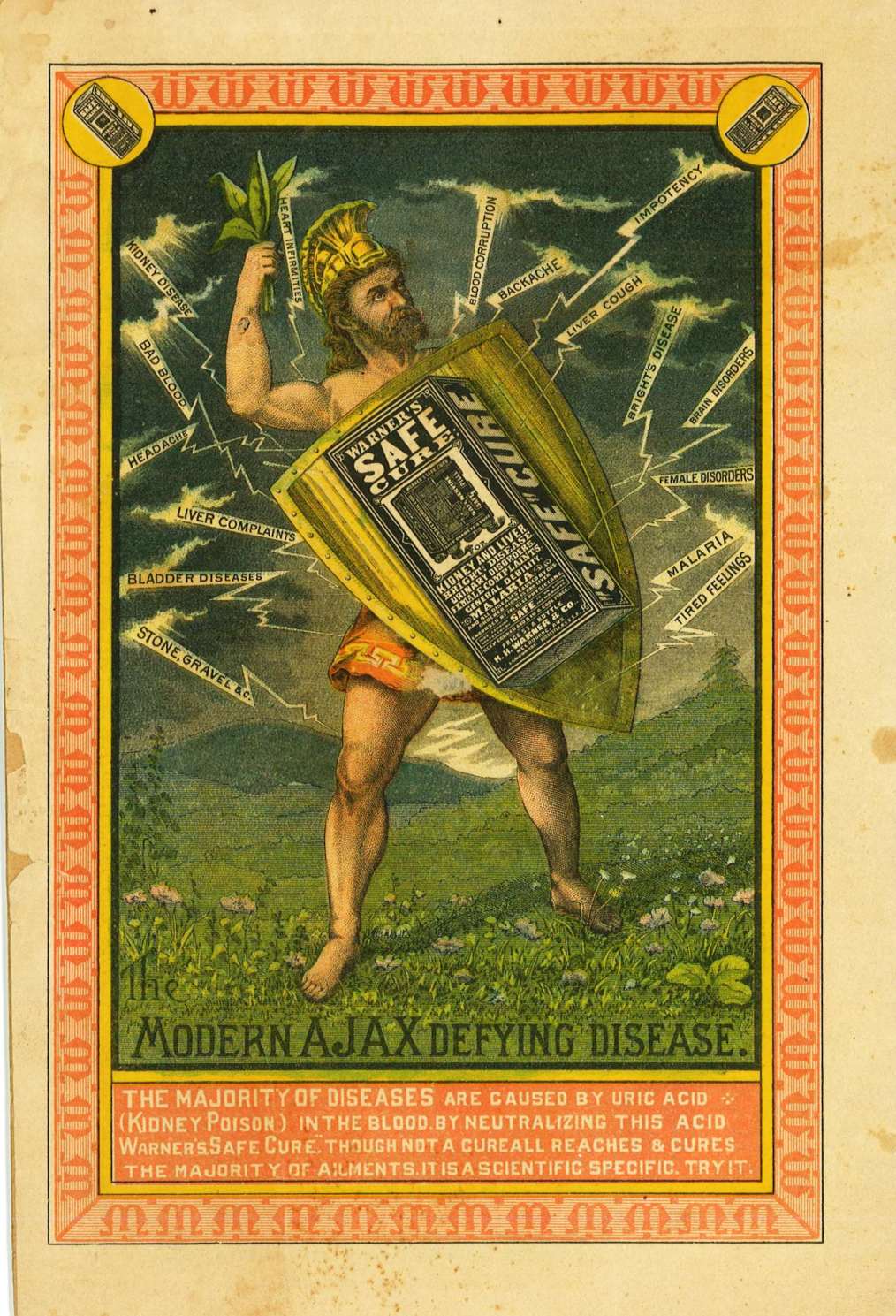

For whatever reason, one of the themes that seems to show up in Warner’s Safe Cure advertising is the notion that Safe Cure provided hope for the hopeless. Indeed the early Safe Cure almanacs contain the story of H. H. Warner’s claim that Dr. Craig’s Cure saved him from certain death as a result of Bright’s Disease. It was for that reason that he claimed to have purchased the remedy to market it to the public at large.

Rescue of the hopeless is often portrayed in a maritime context. I imagine that in the days before GPS and satellite navigation, being lost at sea was the epitome of hopelessness. This is perhaps why Warner seized upon that as a theme. Indeed hope for the hopeless showed up repeatedly in Safe Cure Advertising. Here are a few examples:

Warner’s Safe Cure Ad in The Metropolitan of August, 1890

The above ad was featured in the August, 1890 edition of The Metropolitan and was located by Kevin Taft. It is loaded with symbolism. First, of course, is the anchor, which represents safety in stormy seas. The words “SAFE SURE STEADFAST” speak for themselves as does the rainbow with the words “HOPE HEALTH HAPPINESS”. In essence, the ad offers Safe Cure as hope to navigate the stormy seas of disease. Not exactly subtle, but the Victorians were not known for their subtlety.

Warner’s Safe Cure as a beacon of hope to the distressed appeared on the cover of one of the almanacs in 1887:

Warner’s Safe Cure Almanac – “The Beacon Light of Safety” (1887)

The theme was even included in advertising issued out of Warner’s London Office:

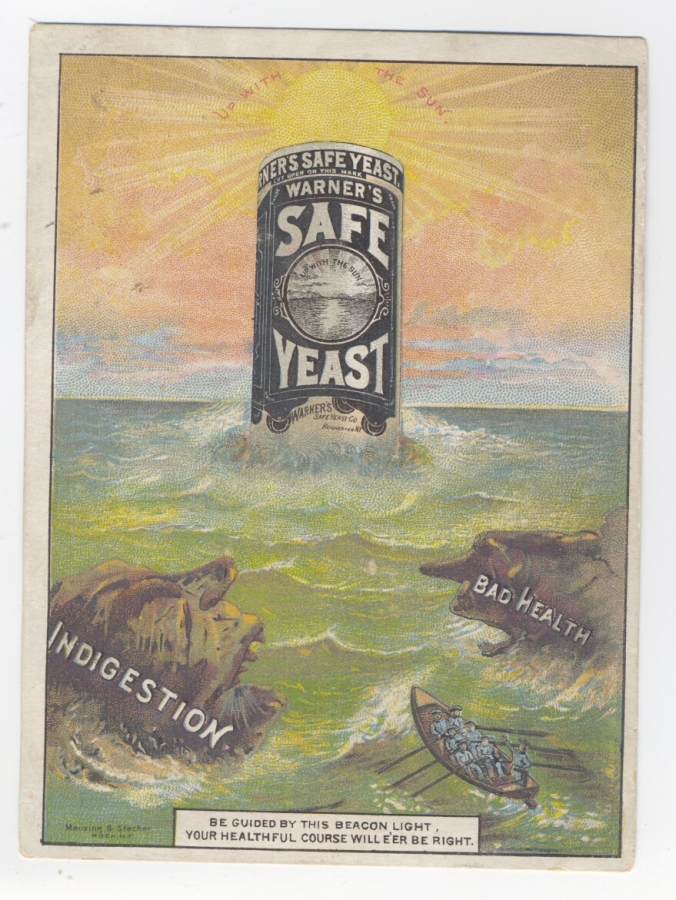

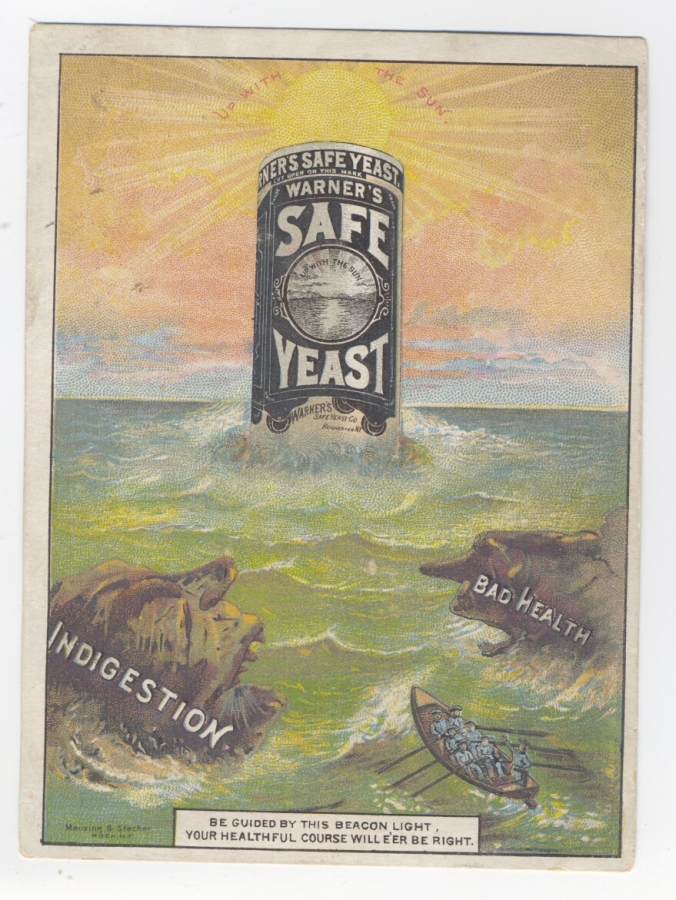

It was also used in the sale of Warner’s Safe Yeast, which claimed “Be Guided By This Beacon Light, Your Healthful Course Will E’er Be Right”. Below is one of the Safe Yeast trade cards that promised to guide distressed mariners through the rocks and shoals of Indigestion and Bad Health.

It was also used in the sale of Warner’s Safe Yeast, which claimed “Be Guided By This Beacon Light, Your Healthful Course Will E’er Be Right”. Below is one of the Safe Yeast trade cards that promised to guide distressed mariners through the rocks and shoals of Indigestion and Bad Health.

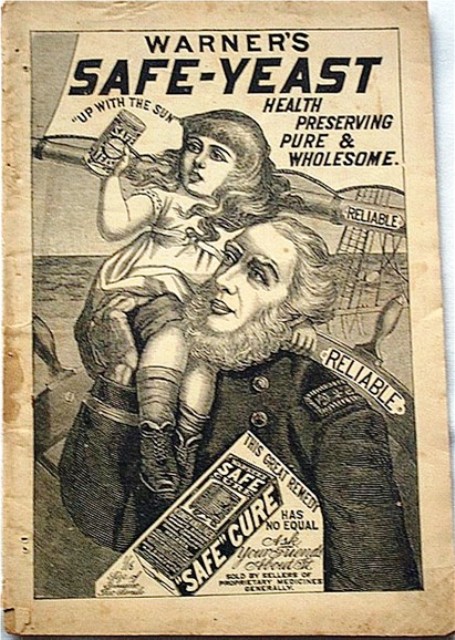

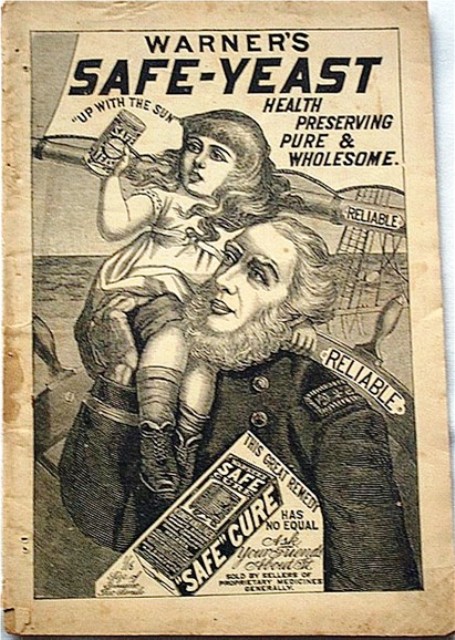

The Safe Yeast/Safe Cure almanac of 1886 featured a girl perched on the shoulders of a sturdy sea captain. Note that the word “Reliable” is prominently featured on the cover of this almanac as well as on the British almanac above. It has an almost subliminal character.

Warner’s Safe Yeast Almanac – “The Old Mariner” (1886)

The constant recurrence of the notion that Warner’s Safe Cure offered the sick safe refuge from the stormy seas of disease was no accident. One must remember that in the 1880’s, the United States was still largely a rural country with a literacy rate far below what it ultimately achieved in the 20th Century. Images were nearly as important as words and Warner knew that. Indeed, the idea of a “Safe Cure” was designed to encourage the public that the product offered a risk-free path to health. Apparently, it was a theme that worked.